Incontinence can severely damage a

patient's perineal skin

and open the door to infection.

Here's how to keep delicate areas dry and intact.

Providing skin care for an incontinent patient

A PATIENT WITH URINARY or fecal incontinence is especially vulnerable to perineal dermatitis. Along with containing leakage and treating the underlying condition, your nursing care plan must include effective strategies for protecting his skin from damage. In this article, we'll discuss how incontinence damages perineal skin and what you can do about it.

Four perineal perils

These four factors contribute to perineal dermatitis in incontinent patients:

* Moisture. Excessive perineal moisture comes from several sources, including urine, perspiration, and liquid stool. The greater the frequency and volume of the incontinence, the greater the risk of skin damage. Containment devices such as pads or briefs, which trap moisture next to the perineal skin and promote perspiration, also raise the risk. Skin that becomes saturated or macerated can't act as a barrier to water, chemicals, and pathogens, and the chemical components of urine or stool irritate the skin. Loss of the skin's normal moisture barrier encourages growth of both normal and pathogenic bacterial flora and fungi. The risk of secondary infection is high in patients with fecal incontinence because this exposes the patient's skin to gastrointestinal flora and digestive enzymes in stool.

* Skin pH. Normal skin has a slightly acidic pH. Perineal skin exposed to urine or stool tends to be alkaline, raising the risk of dermatitis and bacterial proliferation.

* Colonization with microorganisms. Bacterial overgrowth can lead to cutaneous infections, which irritate and inflame the skin and further reduce the skin's efficiency as a barrier. Obese patients who have skin folds within the perineum, immunocompromised patients, and patients with diabetes are particularly prone to secondary cutaneous infection.

* Friction. When moist skin rubs against incontinence containment devices, clothing, and the surface of a bed or chair, friction erodes the skin. In most cases, this erosion remains superficial, but it may involve large areas of perineal skin. Shearing forces are generated when an immobile, incontinent patient is repositioned in a bed or chair and can contribute to pressure injury or ulceration.

The type of incontinence also influences the risk of perineal skin damage and its character. The water in urine contributes to saturation of the perineal skin; urea and ammonia promote alkalinity. Many components of urine promote the overgrowth of microorganisms, particularly if your patient has diabetes and glucosuria.

Fecal incontinence is even more irritating to the perineal skin than urine because feces contain bacteria and digestive enzymes. In a patient with urinary and fecal incontinence, the alkaline environment created by urinary incontinence makes the enzymes in stool even more destructive.

Your goals: Clean and dry

After performing a thorough perineal assessment (see Tips for Assessing the Perineal Skin), formulate a care plan based on your patient's needs. Here are some general guidelines:

* Intact skin and mild to severe urinary incontinence. Clean the perineum daily and whenever you change a moist urinary containment device or after any large episode of urinary leakage. Use a soft, moist cloth or disposable towelette and avoid brisk scrubbing. Apply a moisture barrier (usually a cream or ointment) to help protect the skin from further damage when exposed to urine and stool.

* Fecal incontinence. Clean the perineum daily and after each major incontinent episode, using the method described above. Routinely apply a moisture barrier cream or ointment.

* Urinary and fecal incontinence. Follow the guidelines for fecal incontinence. If the patient has extensive skin erosion that produces exudate. use a barrier haste that absorbs drainage and protects the skin from irritants. (If you use a zinc oxide paste, use mineral oil to remove the paste so you won't damage the skin by scrubbing.) Consult the wound care specialist or primary care provider about applying a compress containing Burow's solution, an astringent that slightly dries and soothes the skin. Follow this treatment by applying a moisture barrier.

* Perineal skin infection. Consult the wound care specialist or primary care provider about localized or systemic treatment.

Now let's look at the products you'll use.

Selecting a skin care product

Perineal skin care products can be divided into three broad categories: cleaners, moisture barriers, and moisturizers.

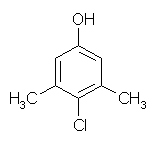

Perineal skin cleaners remove irritants and bacteria from the skin using a surfactant such as sodium lauryl sulfate, triethanolamine lauryl sulfate, or sodium stearate. Skin cleaning products also may contain an antibacterial agent such as triclosan, para chloroxylenol, or chlorhexidine gluconate designed to limit bacterial growth and reduce odor. The routine use of an antimicrobial cleaner remains controversial and should be avoided until more scientific evidence proves its benefit. And beware of fragrances, which can act as irritants and sensitizers, particularly when skin integrity is compromised.

Emollients such as cetyl or stearyl alcohols are a useful addition to skin cleaners because they soften the skin and soothe irritation.

Consider the pH of the skin cleaner: Normal skin pH is 5.5, so you'll want a product with a pH near this value.

The product you select may be packaged as a liquid, emulsion, or foam, or the active products may be impregnated in a soft towelette. Don't use a bar product; it can become a reservoir for bacteria if its used repeatedly without drying, and most bars contain soaps or detergents with a high pH. Besides these disadvantages, soap or detergent bars must be used with a washcloth, and the friction can exacerbate epidermal erosion and remove oils from the patients skin, reducing its barrier efficiency.

Moisturizers, which contain humectants such as glycerin, methyl glucose esters, lanolin, or mineral oil, replace the skin's natural oils and promote the skin's effectiveness as a moisture barrier. Although overhydrated from exposure to urine or stool, the perineal skin may paradoxically be described as "dry" because it lacks these natural oils. Moisturizers can be applied separately, but often are combined with perineal skin cleaners, saving you time.

Moisture barriers, sometimes called skin protectants, are creams or ointments that shield the skin from exposure to irritants or moisture. Active ingredients in moisture barriers include petrolatum, dimethicone, lanolin, and zinc oxide. A moisture barrier may be incorporated into skin cleaners or applied separately. Ointments tend to last longer than creams.

Alternatives to moisture barriers include liquid barrier films, sometimes referred to as skin sealants, which consist of a polymer combined with a solvent (usually alcohol). When applied to the skin, the solvent evaporates and the polymer dries to form a barrier. However, alcohol may be irritating or locally cytotoxic to compromised perineal skin.

Preventive steps

Taking care of the underlying cause of incontinence may require consultation with a urologist, gastroenterologist, urogynecologist, or nurse specializing in continence management; discuss this with the patients primary care provider. In the interim, help the patient obtain and use a containment device that absorbs urine or contains stool and prevents or minimizes skin exposure to these irritants.

Many patients prefer a pad or incontinence brief. Advise female patients to use a device specifically designed for incontinence management, rather than using feminine hygiene products, which aren't well suited for large-- volume urinary leakage. Instead, she should use a product that contains superabsorbent material (a filler capable of absorbing large volumes of urine or liquid) and holds many times its weight in urine.

For patients with mild to moderate urinary incontinence, use a pad that fits into the patients under-- clothing. These pads may adhere to regular underclothing via adhesive strips or fit inside a specially designed stretch undergarment that can be bought separately.

If your patient has urinary and fecal incontinence, or very severe urinary incontinence, use an incontinence brief. Disposable or reusable types are available; most are designed to replace the under-- clothing. The ideal product absorbs urine and fecal leakage, remains hidden underneath clothing, minimizes odor, and doesn't make noise when your patient moves.

Men with urinary incontinence may use a condom catheter. The device should be latex-free and maintain its watertight seal even if the patient has an erection. Some condom catheters may contain a skin adhesive incorporated into the shaft of the condom or have a non-- adhesive shaft with an inflatable self-adhering strap fastener. Consult the wound care or rehabilitation nurse specialist about the proper type of condom catheter if your patient is obese, has a small penile shaft, or is sensitive to the skin adhesive.

Indwelling catheters aren't appropriate for patients with urinary incontinence and irritant dermatitis, secondary dermal skin infections, or erosion. Catheters are reserved for short-term use in patients with higher-stage pressure ulcers. Consult the primary care provider and wound care nurse if your patient with incontinence has a pressure ulcer affecting the perineal skin.

For a patient with severe fecal incontinence and irritated, eroded perineal skin, consider using an anal pouch,.which is similar to the ostomy devices used to pouch colostomies or ileostomies. Successful application of the anal pouch requires creation of a watertight seal, so you should consult the wound care nurse.

If prescribed, a rectal tube, catheter, or similar device may be used for a brief period to divert fecal effluent from the perineal skin. A tube or indwelling catheter with a large internal diameter, usually #22 French or larger, is gently inserted into the rectal vault. If an indwelling catheter is ordered, a retention balloon is inflated and should be deflated periodically to prevent injury to the rectal mucosa. The catheter is attached to a bedside drainage bag that holds at least 2,000 ml.

Tender care

Caring for the incontinent patient with perineal skin problems requires a thorough assessment and good care planning. Using the tips in this article, you can reverse existing perineal skin problems and prevent complications while the underlying condition is brought under control.

SELECTED REFERENCES

Fiers, S., and Thayer, D.: "Management of Intractable Incontinence," In Urinary and Fecal Incontinence: Nursing Management, 2nd edition, D. Dougherty, ed. St. Louis, Mo., Mosby, Inc., 2000.

Nix, D.: "Factors to Consider When Selecting Skin Cleansing Products," Journal of Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nursing. 27(5):260-268, September 2000.

Ratliff, C., and Rodeheaver, G.: "Pressure Ulcer Assessment and Management," Lippincott$ Primary Care Practice. 3(2):242-258, March-April 1999.

BY MIKEL GRAY, RN, CCCN, CUNP, PHD,

FAAN; CATHERINE RATLIFF, RN, CWOCN, PHD;

AND ANN DONOVAN, RN, CWOCN, MSN

Mikel Gray is a professor and nurse practitioner in the department of urology and school of nursing at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, Va. Catherine Ratliff is a wound, ostomy, and continence nurse in the department of nursing and an assistant professor in the school of nursing at the University of Virginia. Ann Donovan is a wound, ostomy, and continence nurse in the department of nursing at the University of Virginia.

Copyright Springhouse Corporation Jul 2002

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved