Bacterial skin infections are very common and trigger destruction of the skin integrity. Impetigo is a consequence of group A β-hemolytic streptococcus or Staphylococcus aureus infection. The clinical presentation in general is very typical and empiric treatment is usually successful. In cases of close contacts such as between classmates, athletes, or soldiers, the prompt recognition and appropriate treatment of the infection may stop an epidemic. We report a group of six soldiers who shared the same military equipment (physical shields) during hand-to-hand combat training. All of the soldiers had skin lesions and two of them suffered from systemic symptoms. Group A β-hemolytic streptococcus and S: aureus were cultured from the impetiginous lesions. All patients recovered after systemic and/or local antibiotic treatments. These cases emphasize the need for the maintenance of proper hygiene throughout the training program to prevent spread of the disease and the importance of rapid diagnosis by bacteriological identification.

Introduction

Skin diseases are common clinical problems encountered in most fields of clinical medicine and are the most frequent reasons for military personnel to seek medical care." The dis ease spectrum observed in the military clinics is very similar to that in a general medical practice. Bacterial and fungal infections, dermatitis and eczema, acne, warts, and nail disorders are the most frequent presentations of skin diseases.1,3-8 Impetigo is a common superficial bacterial infection caused mainly by group A β-hemolytic streptococcus (GABHS) and Staphylococcus aureus (SA), mostly affecting children.3-10 In some reports, group G and group B streptococcus are also involved. Sources for the infection of adults include barbershops, beauty parlors, and crowded housing areas such as military dormitories. Transmission by direct skin contact is possible.

Case Reports

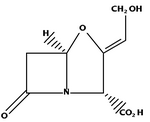

Six soldiers consulted the Dermatology Outpatient Clinic on the same day. All reported that the skin lesions had first appeared 4 to 6 weeks earlier. Two soldiers had systemic symptoms, such as headache, sore throat, and fever. The lesions were clinically diagnosed as bacterial infection resembling furunculosis. It was found that they shared the same military equipment, including physical shields for their faces, knees, thighs, and legs during hand-to-hand combat training. In addition, this group of soldiers shared the same housing during the training. Their lesions appeared on their elbows, knees, and legs (Fig. 1). Sampling of five impetiginous lesions from the patients were swabbed and sent for microbiological analysis. Bacteriological cultures showed growth of SA or staphylococcus coagulase negative (SCN) alone or coexisting with β-hemolytic streptococci. In two patients were found isolates of pure GABHS, in one patient was found SA alone, in one patient was found a combination of GABHS and SA, and in one patient was found GABHS and SCN. Samples from the sixth patient were not sent to the laboratory. Antibiotic sensitivity to the commonly used antibiotics was performed for all bacterial isolates. All isolates of SA and GABHS shared the same antibiogram patterns, respectively. The SA isolates were resistant to penicillin. The GABHS isolates were resistant to tetracycline and ciprofloxacin. The single SCN isolate was resistant to penicillin and erythromycin.

The results are summarized in Table I. All six patients recovered after oral amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (875 mg twice daily) and local mupirocin for 10 days.

Discussion

Infections in general are more common when living under conditions of poor hygiene.11 Superficial and deeper skin injuries (trauma, burns, bite, and scratches) may serve to inoculate organisms into the skin and cause ulcerative lesions.6 Common skin infections include impetigo, cellulitis, erysipelas, folliculitis, and furuncles and carbuncles.1 The classic presentation of impetigo usually is not difficult to diagnose. GABHS causes superficial nonbullous pustules that rupture and form a characteristic yellow-brown honey-colored crust.6'9 Impetigo caused by group G or B streptococci generally forms smaller-sized pustules of fewer numbers. Impetigo caused by staphylococcus results in bullous and nonbullous lesions involving the subcorneal layer of the epidermis. Usual sites of involvement are the face, around the nose and mouth, legs, and other locations.11 Lesions in general are not painful, and patients do not appear to be ill. Cultures of impetiginous lesions often show both SA and GABHS,u as encountered in the cases presented here. In general, streptococcus is the initial pathogen and staphylococcus serves as a secondary colonizer.8 Treatment of all derivatives of impetigo involves improving hygiene first, use of soaks and disinfectants for debridement of adherent crusts, and topical and oral antibiotics.5'8"16 Penicillin is usually effective against streptococci, but in the case of staphylococcus infection another antibiotic should be chosen because of the jS-lactamase present in staphylococcus.5,13,15 In the cases presented here, GABHS was highly susceptible to all of the antibiotics tested, except tetracycline and ciprofloxacin. Impetigo is a severely contagious infection and individuals who have been in very close contact should be always examined.14

Typing of the streptococcus species is important both for selection of the right antimicrobial agent and for identification of the GABHS, since this can sometimes cause acute glomerulonephritis.3,5,12 Serotypes of GABHS producing impetigo are serotypes 49, 55, 57, and 60 strains and M-type 2.12

As suggested by Tan et al.,5 in the case of SA, cephalosporins or cloxacillin are very effective treatments. In some cases, such as secondarily infected ulcers, combination therapy is useful due to frequent mixed infections.5,11,14

According to the antibiogram presented in Table I, the same strain of GABHS or SA was involved in each case. This could lead to the assumption that transmission was from either person-to-person or fomite-to-person. Since we did not have access to the shields for culturing, we could not differentiate between these two modes of transmission.

Other studies have shown a relationship between physical or psychogenic stress and skin infections.18,19 It could be postulated that in these cases the training stress caused the infections. However, this seems unlikely because only these six individuals developed the infection, whereas the other soldiers under the same training conditions did not develop the infection. Also, these six soldiers did not complain of excessive fatigue.

It was found that one of the soldiers had GABHS in his throat. Although generally there are type differences between streptococcal infections of the throat and skin, in this case the possibility of transmission from the throat to the skin cannot be ruled out.11,17,18

In light of this case and other reports,20,21 we would recommend taking cultures randomly from military equipment that is shared between soldiers. In addition, it is worth considering screening for carriers of pathogenic bacteria by taking cultures before each cycle of training.

In conclusion, SA and GABHS are the most frequent agents in skin lesions,5,8,14 and these cases emphasize the importance of rapid diagnosis by bacteriological identification and the need for the maintenance of proper hygiene throughout the training program to prevent spreading of the disease.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Izabella Lejbkowicz and Dr. Anne Kershenbaum for their critical reading.

References

1. Stulberg DL. Pcnrod MA, Blatny RA: Common bacterial skin infections. Am Fam . Phys2002:66: 119-24.

2. Adams BB: Dermatologie disorders of the athlete. Sports Med 2002; 32: 309-21.

3. Higaki S, Kltagawa T, Morohashi M, Yoshida I, Yamagishi T: Characteristics of Streptococcus species isolated from infectious skin diseases. J Dermatol 1999; 26: 803-7.

4. Prose NS, Mayer FE: Bacterial Skin infections in adolescents. Adolesc Med 1990; 1: 325-32.

5. Tan HH, Tay YK, Goh CL,: Bacterial skin infections at a tertiary dermatological centre. Singapore Med J 1998: 39: 353-56.

6. O'Dell ML: Skin and wound infections: an overview. Am Fam Phys 1998; 57: 2424-32.

7. Sadick NS: Current aspects of bacterial infections of the skin. Dermatol Clin 1997; 15: 341-9.

8. Akiyama H, Yamasaki O, Kanzaki H, Tada J, Arata J: Streptococci isolated from various skin lesions: the interaction with Siaphylococciis aureus strains. J Dermatol Sci 1999; 19: 17-22.

9. Brown J, Shriner DL, Schwartz RA, Janniger CK: Impetigo: an update, lnt J Dermatol 2003; 42: 251-5.

10. Hirschmann JV: Impetigo: etiology and therapy. Curr Clin Top Infect Dis 2002; 22: 42-51.

11. Kakar N, Kumar V, Mehta G, Sharma RC. Koranne RV: Clinico-bacteriological study of pyodermas in children. J Dermatol 1999; 26: 288-93.

12. Kobayashi S, Ikeda T, Okada H, et al: Endemic occurrence of glomerulonephritis associated with streptococcal impetigo. Am J Nephrol 1995; 15: 356-60.

13. Nishijim S, Ohshima S, Higashida T, Nakaya H, Kurokawa I: Antimicrobial resistance of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from impetigo patients between 1994 and 2000, Int J Dermatol 2003; 42: 23-5.

14. Laube S, Farrell AM: Bacterial skin infections in the elderly: diagnosis and treatment. Drugs Aging 2002; 19: 331-42.

15. Marchese A, Schito GC. Debbia EA: Evolution of antibiotic resistance in Grampositive pathogens. J Chemother 2000: 12: 459-62.

16. Gisby J, Bryant J: Efficacy of a new cream formulation of mupirocin: comparison with oral and topical agents in experimental skin infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2000; 44: 255-60.

17. Bessen DE, Sotir CM. ReaddyTL, Hollingshead SK: Genetic correlates of throat and skin isolates of group A streptococci. J Infect Dis 1996; 173: 896-900.

18. Cunningham MW: Pathogenesis of group A streptococcal infections. Clin Microbid Rev 2000; 13:470-511.

19. Svejgaard E: The role of microorganisms in atopic dermatitis. Semin Dermatol 1990; 9: 255-61.

20. LaMar JE, Carr RB, Zinderman C, McDonald K: Sentinel cases of communityacquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus onboard a naval ship. Milit Med 2003; 168: 135-8.

21. Vidmar DA, Harford RR, Beasley WJ, Revels J, Thornton SA, Kao TC: The epidemiology of dermatologie and venereologic disease in a deployed operational setting. Milit Med 1996; 161: 382-6.

Guarantor: Flavio Lejbkowicz, PhD

Contributors: Flavio Lejbkowicz, PhD*; Luisa Samet, MSc; Larissa Belavsky, MSc; Ora Bitterman-Deutsch, MD

Clinical Microbiology and Dermatology, Western Galilee Hospital, Naharyia, Israel

* Current address: Flavio Lejbkowicz, PhD, Faculty of Medicine, Technion Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa 31096, Israel; email: flaviolejb@hotmail.com.

This manuscript was received for review in September 2003. The revised manuscript was accepted for publication in October 2003.

Reprint & Copyright © by Association of Military Surgeons of U.S., 2005.

Copyright Association of Military Surgeons of the United States Nov 2005

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved