ABSTRACT

There has been increasing concern about inappropriate or excessive medication of people with learning disabilities. Audits of prescribing practice may guide clinicians towards a more rational use of psychotropic drugs. Most previous studies have come from North America or Europe. This paper reports on a survey of prescribing patterns in an institution that cares for adults with severe to profound learning disabilities in Hong Kong. The survey found that 27% of the 294 hospital patients were receiving psychotropic drugs, but this rate was significantly higher (90%) in the ward for people with challenging behaviours. Most patients (67%) received a single psychotropic drug, 26% received two and 7%, three. Around half the patients (151) had epilepsy, of whom 90% received anticonvulsants. Of these, 52% received a single anticonvulsant, 37% received two and 11% received three or more. Dosages were generally within the recommended ranges.

This survey revealed several good aspects of prescribing practice at Siu Lam Hospital, but also areas that need improvement. The latter include a drug-reduction programme for the people with challenging behaviours, trials of drug-free periods for seizure-free patients receiving anticonvulsants and replacement of phenytoin and phenobarbitone with safer alternatives.

INTRODUCTION

Prescribing patterns among people with learning disabilities have long been a focus of concern in the United States and United Kingdom (Poindexter, 1989; Ahmed et al, 2000). Themes explored have included over-medication in general, polypharmacy, inappropriate dose levels, types of drug used and reasons for prescribing. In addition, side-effects of psychiatric drugs have received growing attention (Kalachnik, 1999). Several authors reporting from a variety of settings have found good evidence that institutionalised patients with learning disabilities are over-medicated (Brooke, 1998; Rinck et al, 1993). Surveys have shown that 30-50% of this population receive psychotropic medication, 2545% receive anticonvulsants and a combined total of about 60% receive some form of psychoactive medication (Sewell &Werry, 1976; Aman, 1987; Burd et al, 1991). However, little research has been published on this subject from Asia.

Medication is often prescribed to control challenging behaviour, but there is little evidence that the drugs most commonly prescribed are effective for this purpose (Schaal & Hackenberg, 1994). The use of drugs for people with learning disabilities should be based on accurate diagnosis and sound pharmacological principles. Audits of prescribing practice may guide clinicians towards a more rational use of psychotropic drugs (Barbui et al, 1999). For this reason a survey of prescribing patterns at the author's workplace (Siu Lam Hospital) was undertaken to explore the issues raised above.

METHODS

Siu Lam Hospital (SLH) is the only hospital under Hong Kong's Hospital Authority that provides rehabilitative and infirmary services exclusively to adults with severe to profound learning disabilities (SLD). As at December 1998, the hospital had 300 beds and a staff of 312, and the patient occupancy rate was 97.2% over the year. The drug budget for 1998-9 was US$105,600 (HK$823,680), which represented about 11 % of the total hospital budget.

A point prevalence study was carried out on 1st December 1998 on the 294 SLD patients in the hospital on that date. The daily dose of all medication was recorded from medication cards.

Patient population

The population comprised 195 male and 99 female patients. Their mean age was 35.1 years. Of these 294 patients, 9% had been resident in the hospital for up to four years, 42% had stayed between four and eight years, and 49% had stayed more than eight years. About half the patients (55%) were not ambulant; either they were confined to bed or they could only tolerate sitting for less than two hours, as assessed by physiotherapists. Nearly all the patients (93%) had communication and speech problems. They resided in six wards designated A to F. Ward A is reserved for patients with challenging behaviour. All patients had severe or profound learning disability, according to DSM-IV. The causes of their learning disability were not analysed, since all patients had been admitted in adulthood.

Admission criteria for the hospital are that patients must come into one of the following categories:

* have at least two kinds of physical disability

* be confined to bed

* require constant nursing care

* have epilepsy that is not well controlled by treatment

* require special feeding methods

* exhibit severe behavioural problems of a violent nature.

There is no facility for acute treatment at SLH.

Medications

Using the convention of Aman & Singh (1988), a psychoactive drug was defined as one that modifies behaviour, emotion or cognition, regardless of the purpose for which it was prescribed. A psychotropic drug was defined as one that is prescribed for the purpose of modifying behaviour, emotion or cognition. An anticonvulsant was defined as a medication that has the primary purpose of controlling seizures.

RESULTS

Psychoactive medication

Overall, 63% of patients (185/294) were receiving psychoactive medication. Details are shown in Table 1, below.

All patients (30) on the ward for people with challenging behaviour (Ward A) were receiving some form of psycho active medication, and 27 (90%) were on psychotropics. The rate of prescribing for Ward A was significantly greater than that for the rest of the hospital (p

Psychotropics

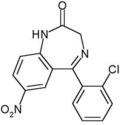

Of the 294 patients, 80 (27%) were receiving psychotropic drugs. Pericyazine, haloperidol and chlorpromazine were the most commonly prescribed. Dosage details are shown in Table 2, below. A total of 70 patients received phenothiazines, 27 received butyrophenones and one was receiving an atypical antipsychotic.

Fifty-four patients (67%) received a single psychotropic drug, 20 (26%) received two, and six (7%) received three. Of the patients receiving psychotropic medication, 41 (48%) were also prescribed the anticholinergic benzhexol (trihexyphenidyl).

Anticonvulsants

Of the 151 patients with epilepsy, 136 (90%) were receiving anticonvulsants (46% of the total population). Around half (70, 52%) received one anticonvulsant, 51 (37%) received two, 14 (10%) received three and one patient (1%) received four anticonvulsants.

Other medications

Eight patients (three per cent) received benzodiazepines (clonazepam three, diazepam three, lorazepam one, nitrazepam one). Five patients (two per cent) received antidepressants (mianserin three, amitryptiline two). Two patients were receiving methylphenidate and one was receiving lithium carbonate.

Cost of treatments

The average monthly drug expenditure per patient at SLH for 1998/9 was HK$177, compared with HK$270 in a major psychiatric hospital. These figures were $168 and $380 respectively in the first quarter of 1999/00.

DISCUSSION

Most studies of prescribing frequency have been performed in the United States. This is the first audit of prescribing for adults with SLD in Hong Kong. It is therefore interesting to compare the findings at SLH with those from other centres. The total number of patients receiving some form of psychoactive medication (63%) was similar to the average of 60% found in many other studies. However, the proportion receiving psychotropic drugs (27%) is lower than in other studies, which have shown that 40-50% of in-patients with learning disabilities receive psychotropics. For example, 48% of patients in an English hospital with similar characteristics to those at SLH were receiving psychotropics (Kiernan et al, 1995).

All SLH patients had inadequate ability to express their thoughts and feelings because of the severity of their learning disability. This raises issues about consent to medication. However, the decision to prescribe psychoactive medication was based on a comprehensive assessment of the individual's emotional and behavioural disturbance. Treatment with psychoactive drugs was an integrated part of other concurrent treatments such as behavioural therapy, use of multi-sensory stimulation, music therapy and hydrotherapy. Good interdisciplinary communication was achieved through daily clinical ward rounds and close liaison with nurses and all therapists. Clinical observations during treatment were documented in each patient's casenotes, including the effects of treatment. Drugs were reviewed at least every six weeks. Monthly clinical management meetings were held, chaired by the clinical co-ordinator with the active participation of all physicians, nurse managers and allied health members. These meetings serve as an open forum to discuss patients' progress and review drugs. Sometimes patients' families are invited to attend. The target was to reduce reliance on antipsychotic medication to control challenging behaviour. Growing awareness of the potentially harmful effects of these drugs on patients was noted. Availability of other types of treatment to complement drug therapies enabled more choices to be offered to patients.

The significantly higher proportion of patients in Ward A receiving psychotropic drugs is not surprising, since this is a ward designated for people with challenging behaviour. No patients were receiving doses greater than those recommended in the British National Formulary (BMA, 1997) and the majority (67%) were receiving only one psychotropic drug. The proportion of patients receiving an anticholinergic agent (48% of those receiving psychotropic drugs) is within the range of other studies (10-50%) (Branford et al, 1993). Anticholinergics are most often used to help control extra-pyramidal or 'Parkinsonian' side effects (such as tremors, shaking and movement problems).

However, the proportion of patients receiving anticonvulsants (46%) was slightly higher than that reported for other countries (25-45%), but this may simply reflect the high percentage of patients with epilepsy (51%) in the SLH population (SLH was designed to treat intractable epilepsy). The proportion of patients receiving phenytoin (51%) may be a cause for concern since, despite its wellaccepted efficacy to control seizures, phenytoin has been associated with behavioural side-effects (Hanzel et al, 2000). Patients with learning disability may also be at increased risk of phenytoin encephalopathy (Livanainen Matti, 1998).The use of phenobarbital should also be reviewed, in the light of its tendency to exacerbate behavioural disorders (Alvarez Norbeto, 1998).

The proportion of patients receiving more than one anticonvulsant at SLH were comparable to, or perhaps a little lower than, those in other institutions (50% of patients received only one, 38% received two). However, this finding must not give rise to complacency, and the introduction of more effective anticonvulsants may permit further reduction in polypharmacy.

The proportion of patients receiving benzodiazepines (three per cent) was lower than in most other published studies, which report rates of 10-20% (Branford, 1994). Benzodiazepines were used to treat anxiety and were prescribed after a clear diagnosis over a short period. The low rate of benzodiazepine use may represent good practice, in view of concerns about the risks of dependence (CSM, 1988). Similarly, the rate of antidepressant use (only five patients, or two per cent) is lower than that in other studies, which have found rates from three per cent (Fischbacher, 1987) to nine per cent (Findholt & Emmett, 1990). This low rate of antidepressant prescribing may reflect underdiagnosis of depression among the patient population at SLH. Other drugs such as methylphenidate and lithium were prescribed very rarely (one per cent). The low use of stimulants such as methylphenidate reflects similarities between Hong Kong and British practice, but contrasts with the United States, where such drugs are used more widely.

Only one patient was receiving an atypical antipsychotic. There have been recent concerns, expressed particularly by patients' relatives and learning disability pressure groups, that such drugs are being withheld from patients in public hospitals because of cost considerations. The drug-purchasing policy in SLH has always been uninfluenced by cost considerations, so long as well-established clinical benefits can be demonstrated. Careful pharmacoeconomic evaluations are needed to determine whether the benefits of atypical antipsychotics are worth the extra cost. In particular, their benefits in the population of people with severe learning disabilities have yet to be firmly established (Taylor & Aitchison, 1999), although one review has concluded that atypical antipsychotics are better tolerated and more effective in patients with learning disabilities (Conner & Posever, 1998).

The average monthly drug costs at SLH appear relatively stable compared with those at a major Hong Kong psychiatric hospital, which had a marked increase in expenditure from 1998/9 to 1999/2000. This may have been due to the increased use of atypical antipsychotics in the psychiatric hospital.

As the community care model of psychiatric service is being adopted in Hong Kong, bed numbers in psychiatric hospitals are set to decrease. However, psychiatric services for people with learning disabilities have increased, due to growing community awareness of challenging behaviour. Assessment and treatment beds for people with learning disabilities are also planned to increase to meet this demand.

Surveys of prescribing patterns for people with learning disabilities living in institutions have been published increasingly frequently since the 1970s. Most of these publications originate from US institutions, where an annual audit of drug use is often routine. Aman & Singh (1988) reviewed 35 surveys of such prescribing, and concluded that the overall prescription rates were excessive. They noted that the issues surrounding medication are complex, and the role of medication can only be determined by the collection of reliable data about effects, costs and clinical benefits.

In line with several other studies, this study showed that specific indications for psychotropic medication in patients with SLD are not well established (Aman & Singh, 1988; Lipman, 1970). This aspect of the treatment of patients with SLD has attracted considerable criticism. However, it is well to remember that this population presents special problems. Not only do they typically have cognitive dysfunction (usually in conjunction with behavioural or psychiatric disturbances), but also we lack clear direction when it comes to differential diagnosis.

There is general agreement about the need to reduce to a minimum the prescription of psychoactive drugs for people with SLD (Jancar, 1970; Kirman, 1975; Fielding, 1980). Experience at SLH indicates that psychotropic drugs do have a place in the care of these patients, but they should be used cautiously and only where they are judged to be effective. We recommend that prescribing of psychotropic drugs should be part of a multidisciplinary approach involving other therapeutic measures. The team should ensure that medication is not prescribed in lieu of individual programme plans, interdisciplinary co-ordination, environmental improvements or staff training. It is also important that the medical chart contain documentation of the purpose for which the medication is prescribed and any evidence of its effectiveness, or lack thereof, for the individual patient. The goal should always be to achieve the lowest dose of the most appropriate medication needed to manage symptoms, and the elimination of medication altogether whenever possible.

Drugs are valuable resources, not only because of their cost, but also in terms of the professional time involved in prescribing, dispensing and administration. Giving sub-therapeutic doses is thus a waste of resources and may also subject patients to unnecessary risk. The prescribing philosophy encouraged at SLH has always been: 'When in doubt, don't prescribe'. It is a conservative approach, but one that has stood the test of time. A sample of patients' current medication is reviewed at monthly clinical management team meetings to ensure that minimally effective doses are given and redundant medications are stopped.

People with SLD are particularly at risk from the side-effects of medication, as they are often unable to complain about them. It is therefore very important to maintain a high degree of vigilance for any possible adverse drug reaction. Nursing staff and health care assistants are trained to detect signs of adverse drug reactions as early as possible, for example by issuing check-lists of possible sideeffects of all medications administered on each ward. These check-lists are also issued to family members when patients leave the hospital for home leave.

Monitoring drug concentrations may help reduce toxicity. At SLH, anticonvulsant levels are checked at least every six months, and more frequently if indicated. Lithium levels are assessed each month. However, staff are alerted to the importance of clinical observation for symptoms of toxicity, rather than relying on blood-level monitoring. People with learning disabilities may be vulnerable to central nervous system side-effects of anticonvulsants, even at therapeutic levels (Chadwick, 1987).

CONCLUSIONS

This survey of prescribing patterns has revealed many good aspects of practice at SLH, but also highlights areas that need improvement. The following goals are suggested.

* Institute drug-reduction programmes, especially in Ward A (for people with challenging behaviours).

* Institute trials of drug-free periods for seizurefree patients on anticonvulsants.

* Replace phenytoin and phenobarbitone with safer drugs.

* Anticholinergic prescription should not be routine, but needs stricter justification.

* An annual prescription review should be implemented.

* Wider use of atypical antipsychotics should be considered.

References

Ahmed Z, Fraser W, Kerr M et al (2000) Reducing antipsychotic medication in people with a learning disability. British Journal of Psychiatry 176 42-6.

Alvarez Norberto (1998) Barbiturates in the treatment of epilepsy in people with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 42 (Suppl 1) 16-23.

Aman MG (1987) Overview of pharmacotherapy current status and future directions. Journal of Mental Deficiency Research 31 121-30.

Aman MG & Singh N (1988) Patterns of drug use, methodological consideration, measurements techniques and future trends. In: M Aman & N Singh (Eds) Psychopharmacology of Developmental Disabilities. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

Barbui C, D'Avanzo B, Frattura L & Saraceno B (1999) QUALYOP project 2. Monitoring the dismantling of Italian psychiatric hospitals. Psychotropic drug use in 1072 inpatients. Pharmacoepidemiology & Drug Safety 8 (5) 331-7.

Branford D, Collacott RA &Thorp C (1993)The prescribing of neuroleptic drugs for people with learning disabilities living in Leicestershire. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 26 233-45.

British Medical Association (BMA) (1997) British National Formulary. London: British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain.

Brooke D (1998) Patients with learning disability at Kneesworth House Hospital. The first five years. Psychiatric Bulktin 22 29-32.

Burd L, Williams M, Klug MG et al (1997) Prevalence of psychotropic and anticonvulsant drug use among North Dakota group home residents. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 41 488-94.

Chadwick DW (1987) Overuse of monitoring of blood concentrations of antiepileptic drugs. British Medical Journal 294 723-1.

Committee on Safety of Medicines (1988) Benzodiazepines: dependence and withdrawal symptoms. Current Problems 21. London: CSM.

Connor DF & PoseverTA (1998) A brief review of atypical antipsychotics in individuals with developmental disability. Mental Health Aspects of Developmental Disabilities 4 93-102.

Fielding LT (1980) An assessment programme to reduce drug use with the mentally retarded. Hospital and Community Medicine 31 771-3.

Findholt N & Emmett C (1990) Impact of interdisciplinary review on psychotropic drug use with persons who have mental retardation. Mental Retardation 28 41-6.

Fischbacher E (1987) Prescribing in a hospital for the mentally retarded. Journal of Mental Deficiency Research 31 17-49.

Hanzel TE, Bauernfeind JE, Kalachnik JE & Harder SR (2000) Results of barbiturate drug discontinuation on antipsychotic medication dose in individuals with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 44 155-63.

Jancar J (1970) Gradual withdrawal of tranquilizers with the help of ascorbic acid. British Journal of Psychiatry 117 238-9.

Kalachnik JE (1999) Measuring side-effects of psychopharmacologie medication in individuals with mental retardation and developmental disabilities. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews 5 (4) 348-59.

Kiernan C, Reeves D & Alborz A (1995) The use of anti-psychotic drugs with adults with learning disabilities and challenging behaviour. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 39 263-74.

Kirman B (1975) Drug therapy in mental handicap. British Journal of Psychiatry 127 545-9.

Lipman RS (1970) The use of psychopharmacological agents in residential facilities for the retarded. In: P Menolascino (Ed) Psychiatric Approaches to Mental Retardation. New York: Basic Books.

Livanainen Matti V (1998) Phenytoin effective but insidious therapy for epilepsy in people with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 41 (Suppl 1) 24-31.

Poindexter AR (1989) Psychotropic drug patterns in a large ICF-MR facility. A ten-year experience. American Journal of'Mental Retardation 93 (6) 624-6.

Rinck C, Guidry J & Calkins CF (1993) Review of state practices on the use of psychotropic medication. American Journal of Mental Retardation 93 657-68.

Schaal DW & HackenbergT (1994) Toward a functional analysis of drug treatment for behavior problems of people with developmental disabilities. American Journal of Mental Retardation 99 (2) 123-4.

Sewell J & Werry JS (1976) Some studies in an institution for the mentally retarded. New Zealand Medical Journal 84 317-9.

Taylor D & Aitchison KJ (1999) The pharmacoeconomics of atypical antipsychotics. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice 3 (4) 237-48.

Woon Chu Winston Lim

CLINICAL CO-ORDINATOR, Siu LAM HOSPITAL, HONG KONG

Copyright Pavilion Publishing (Brighton) Ltd. Oct 2005

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved