Memorable medication

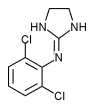

Clonidine, a drug widely prescribed for lowering blood pressure, has now been shown to enhance the memory of elderly monkeys and people with Korsakoff's syndrome, a memory disorder. Clonidine interests scientists because it alters levels of norepinephrine, a pervasive chemical messenger in the brain that is in short supply in Alzheimer's patients as well as in those with Korsakoff's. Further work with clonidine may point toward a treatment for Alzheimer's, a disease that brings senility and slow death to more than 100,000 people in this country each year.

Neuroscientists Amy Arnsten and Patricia Goldman-Rakic studied the effect of clonidine on the "spatial working memory' of five older female monkeys. Spatial working memory allows people to recall such things as were they left their housekeys or parked their car outside a shopping mall. Because the location of familiar objects will often change, this memory requires selective forgetting as well as constant updating. This kind of memory generally declines as both monkeys and people age, but its rapid deterioration is a harbinger of Alzheimer's disease.

In one experiment, the monkey watched as a raisin or peanut was dropped in one of two dishes. Each dish was then covered with cardboard, and a screen lowered in front of the entire setup. After a varying delay, the screen was raised and the monkey was allowed to choose a dish. Monkeys injected with a salt-solution placebo had trouble selecting the dish with the raisin after a delay of more than a few seconds. But when the same monkeys were given an optimal dose of clonidine, all five improved. In fact, four achieved near-perfect performance even on the longest delays.

The trick was to find each monkey's optimal dose. Clonidine is a sedative, and at higher doses, Arnsten says, "the monkeys' eyes close, and it's a real fight for them between the desire for a raisin and the desire to sleep.' As the animals developed a tolerance to the drug's sedative effects, the researchers were able to pinpoint a middle dose at which each animal performed well yet was still alert, though "a little quieter' than her undrugged sisters.

Arnsten and Goldman-Rakic say that clonidine's effects on memory are unrelated to lowered blood pressure, reduced anxiety or any of the drug's other sedative effects. In another experiment, they taught the same monkeys to discriminate between two simple patterns--a plus sign and a square--a task that does not rely on working memory. The not-so-old monkeys in the group had no trouble learning the task whether they were injected with clonidine or the salt solution. But the oldest monkeys simply couldn't learn the task, and clonidine neither helped nor hurt.

Arnsten and Goldman-Rakic's findings fit with recent studies on people with Korsakoff's syndrome. Stemming from a severe vitamin deficiency, the condition is usually seen in long-term alcoholics. Patients have difficulty learning new information and often forget things that they once knew. A quick vitamin fix doesn't help these people because the deficiency has damaged norepinephrine-producing cells in their brains. But as neurologist William McEntee and psychologist Robert Mair recently discovered, clonidine improves their ability to learn new information.

For many years scientists have known that clonidine can reduce levels of norepinephrine in the brain. When recently it was discovered that the drug helped monkeys and people with memory disorders associated with low norepinephrine, scientists were first incredulous and then baffled. How could a drug that further diminished norepinephrine enhance memory?

Arnsten and Goldman-Rakic speculate that clonidine's overall effect on the brain is very much dose-dependent. Clonidine binds with sites on both the transmitting and receiving ends of the minute gap between nerve cells. At low doses, clonidine seems to shut off the release of norepinephrine into the gap by binding on the transmitting end. At high doses, clonidine seems to favor sites on the receiving end, and by substituting for the missing norepinephrine, "fools' these sites into reacting as though there is plenty of it in the gap.

Arnsten and Goldman-Rakic believe that these studies suggest new strategies for treating memory disorders in older people and Alzheimer's patients. While other researchers have begun the clinical testing that precedes the widespread use of any drug, Arnsten and Goldman-Rakic are back with their monkeys looking for a new drug: one that will provide the cognitive benefits without sedation.

COPYRIGHT 1986 Sussex Publishers, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group