Prescription drug abuse can involve medications not usually considered to have addictive potential. Clonidine is a rare, but important, atypical drug of abuse. Atypical prescription abuse was discovered in a patient who had a history of alcohol and drug abuse. Clonidine produced a state that the patient identified as similar to the condition resulting from the use of opioids. This article offers a framework for identifying atypical prescription drug abuse and suggests guidelines for prevention and management.

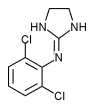

Clonidine (Catapres) is a centrally acting [alpha.sub.2]-adrenergic agonist. It is traditionally used as an antihypertensive agent and, to a lesser extent, to alleviate the symptoms of opioid withdrawal. Clonidine is not a scheduled drug and is not generally considered to have significant addictive potential. Cases of clonidine abuse have been reported, however, suggesting that high doses of the drug may have sedative or euphoric effects.[1-3] Awareness of atypical prescription drug abuse can aid family physicians in the prevention, detection and management of the problem.

Illustrative Case

A 42-year-old man who had recently been admitted to a medical inpatient unit was referred for psychiatric consultation because he threatened to overdose with antihypertensive medication. This patient had a long history of polysubstance abuse, including amphetamines, heroin, opioids, benzodiazepines, cocaine and marijuana. Over the past several years, the patient had developed primary hypertension. About three years before, he had started taking clonidine, 0.3 mg daily, to control his blood pressure.

The patient gradually developed a pattern of clonidine prescription abuse. His abuse was prompted by a stressful social situation. In an attempt to relieve his distress, he impulsively took eight to 10 clonidine tablets, 0.3 mg each (2.4 mg to 3.0 mg total), at one time. He did not think this was likely to relieve his distress but did not know what else to do. He was pleasantly surprised when he found that this dosage produced what he described as a "nod" effect, similar to what he had experienced with morphine. He described this effect as a state in which the user becomes "sleepy and in dreamland, like floating on a cloud but still not unconscious--Nirvana." He insisted it was better to use clonidine than heroin, because clonidine did not make him feel sick afterward. Even better was the fact that the effect lasted up to one-half day. While taking this high dosage of clonidine, he reported experiencing fatigue, decreased appetite, drowsiness, blurred vision, slurred speech and euphoria. He denied any withdrawal symptoms except for insomnia.

Following his initial experience with a high dosage of clonidine, he developed a pattern of behavior that maximized his supply of the drug. He found a way to have two different pharmacies fill prescriptions. He would use a month's supply of clonidine in a week. Because clonidine was an atypical drug of abuse, he found it easy to persuade his physician to give him replacement prescriptions for ones that he claimed were lost. When he was out of money to purchase illicit drugs, he used clonidine to moderate the withdrawal symptoms. When he was unable to secure clonidine, he increased his use of opiates and cocaine. He was so satisfied with this method of using clonidine that he introduced two of his friends to the practice. He reported that these friends are now regular users of high dosages of clonidine.

Eventually, the man's physician discovered his abuse of clonidine and switched him to a patch form. The patient found that this route of drug administration failed to produce the desired effect. He tried applying several patches at a time, but that also failed to give him the same effect. Unfortunately, the patch form also failed to control his hypertension, probably because of problems with compliance.

The patient was admitted to an inpatient drug treatment program several days before his medical hospitalization. His transfer to a medical facility was precipitated by the sudden onset of night sweats, fever, chills, hypertension and bleeding gums. In the course of the workup, the medical staff decided to switch the patient from clonidine patches to a calcium channel blocker. In an attempt to persuade his physician to put him back on clonidine, the patient threatened to take all of the calcium channel blocker pills at one time. The medical team considered this a suicide threat and requested psychiatric consultation.

Psychiatric consultation confirmed the clonidine abuse. In addition, the patient's psychiatric history included multiple nonserious suicide attempts, incarcerations for drug violations and domestic abuse directed toward live-in companions. He had a long history of cocaine and opiate dependence. In addition, his history was consistent with the diagnosis of borderline personality disorder. Psychiatric consultation confirmed that there was no serious suicide risk, major depression or need for psychiatric hospitalization. It was recommended that the patient not be prescribed clonidine again because of his pattern of abuse and the possible medical complications of clonidine abuse.

Discussion

This illustrative case resembles cases of clonidine abuse described elsewhere.! The abuse reportedly developed in patients with preexisting drug dependence, including opiate dependence. For example, Lauzon's patients who abused clonidine were both participating in a methadone maintenance program. Dosages used by all three subjects ranged from 1 to 3 mg of donidine, which is 10 to 15 times the usual dosage for the treatment of hypertension.

The common history of preexisting opioid abuse suggests that there may be an important learning or priming component to clonidine abuse. Clonidine abuse has not been reported in patients with no history of previous opiate abuse. In addition, opiate abusers are more likely to be exposed to clonidine because of its use for opiate withdrawal.[4-6]

In Lauzon's cases, clonidine abuse was described in the context of concurrent use of other drugs. This concurrent use pattern was not noted in our patient

It may be difficult to determine when prescription drug use becomes prescription drug abuse. Although a physician's level of awareness of abuse potential is high for scheduled drugs like benzodiazepines and narcotics,[7-9] our illustrative case suggests that certain nonscheduled drugs should also be closely monitored. Table 1 lists behaviors and patterns consistent with abuse of prescription medication.[10]

Family physicians can reduce the risk of atypical drug abuse by remaining aware of the problem and the pharmacologic agents that have been abused.[12] Although clonidine abuse appears to be rare, clonidine can be added to the list of agents that should be monitored in patients with a history of substance abuse, especially narcotic abuse. Using high dosages of clonidine offers the potential for significant medical complications, including hypotension. Behaviors associated with prescription drug abuse should be investigated, even for compounds not commonly thought to be drugs of abuse. Successful treatment begins with reducing the patient's prescription access to the atypical drug of abuse and initiating standard treatment protocols for the management of substance abuse. Depending on the extent of the abuse, treatment may include gradual tapering, symptomatic treatment of any withdrawal symptoms, counseling and enrollment in a formal substance abuse program.

REFERENCES

[1.] Lauzon P. Two cases of clonidine abuse/dependence in methadone-maintained patients. J Subst Abuse Treat 1992;9:125-7. [2.] Sharma A, Newton W. Clonidine as a drug of abuse. J Am Board Fam Pract 1995;8:136-8. [3.] Raber JH, Shinar C, Finkelstein S. Clonidine patch ingestion in an adult. Ann Pharmacother 1993; 27:719-22 [Published erratum appears in Ann Pharmacother 1993;27:1143]. [4.] Gold MS, Redmond DE Jr, Kleber HD. Clonidine blocks acute opiate-withdrawal symptoms. Lancet 1978;2(8090):599-602. [5.] Gold MS, Pottash AC, Sweeney DR, Kleber HD. Opiate withdrawal using clonidine. A safe, effective, and rapid nonopiate treatment. JAMA 1980; 243:343-6. [6.] Gold MS, Redmond DE Jr, Kleber HD. Noradrenergic hyperactivity in opiate withdrawal supported by clonidine reversal of opiate withdrawal. Am J Psychiatry 1979;136:100-2. [7.] Finlayson RE, Davis LJ Jr. Prescription drug dependence in the elderly population: demographic and clinical features of 100 inpatients. Mayo Clin Proc 1994;69:1137-45. [8.] Barnas C, Whitworth AB, Fleischhacker WW. Are patterns of benzadiazepine use predictable? A follow-up study of benzodiazepine users. Psychopharmacology 1993;111:301-5. [9.] Miller NS, Gold MS. Abuse, addiction, tolerance, and dependence to benzodiazepines in medical and nonmedical populations. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 1991;17:27-37. [10.] Voth EA, Dupont RL, Voth HM. Responsible prescribing of controlled substances. Am Fam Physician 1991;44:1673-8. [11.] American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association, 1994:270-2. [12.] Finch J. Prescription drug abuse. Prim Care 1993; 20:231-9.

The Authors EDMUND C. DY, M.D. is a fourth-year resident in psychiatry at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics. He graduated from Southern Illinois University School of Medicine, Springfield.

WILLIAM R. YATES, M.D. is associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Iowa College of Medicine and director of the Psychiatry Consultation Service at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, both in lowa City. He graduated from the University of Nebraska College of Medicine, Omaha, and completed a residency in family practice at the Lincoln (Nebr.) Medical Education Foundation. He also completed a residency in psychiatry at the University of lowa Hospitals and Clinics, lowa City. Dr. Yates is board-certified in family practice and psychiatry.

Address correspondence to William R. Yates, M.D., Dept. of Psychiatry Administration, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, 200 Hawkins Dr., #2887-JPP, Iowa City, IA 52242.

COPYRIGHT 1996 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group