To the Editor:

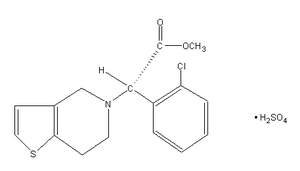

In their recent article in CHEST (September 2004) (1) on antithrombotic therapy, Stein et al recommended that clopidogrel be added to aspirin for 9 to 12 months in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) following a non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTE-ACS). The authors assigned this recommendation a grade of 1A, suggesting that the benefits derived from this strategy are clear and are supported by randomized clinical trial data without important limitations. (2) The authors based this recommendation on data from the Clopidogrel in Unstable Angina to Prevent Recurrent Events (CURE) trial. (3)

Because no prospective, randomized clinical trials have specifically examined the role of clopidogrel in patients following CABG, the authors are correct in basing their recommendations on data abstracted from the CURE trial. Nevertheless, it is our opinion that currently available trial data do not support a grade 1A recommendation. In fact, recent data have suggested that postoperative treatment with clopidogrel provides no substantial clinical benefit and, if anything, increases the risk of serious bleeding. Because of this, it is our opinion that clopidogrel should not be routinely used after CABG following an NSTE-ACS.

In the CURE trial, (3) 12,562 patients with NSTE-ACS were randomized to treatment with clopidogrel (300 mg initially followed by 75 mg daily) plus aspirin (75 to 325 mg daily) vs aspirin alone (75 to 325 mg daily). The primary outcome was a composite of cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or stroke. Patients randomized to receive dual antiplatelet therapy (clopidogrel and aspirin) had a 20% relative risk reduction (RRR) in the primary end point at a mean of 9 months (9.3% vs 11.4%, respectively; p < 0.001), with greater benefit (44% RRR) noted in those patients undergoing revascularization (ie, CABG or percutaneous coronary revascularization). Despite this, the CURE trial investigators cautioned against the interpretation of these latter results, "given the large numbers of subgroup analyses that were performed."

Although the CURE trial did not initially report the results of the primary end point for those who underwent CABG subsequent to study enrollment, these results were recently published by Fox et al (4) In this post hoc analysis, the addition of clopidogrel to aspirin led to an insignificant 11% RRR in the primary outcome among those undergoing CABG a median of 25.5 days after randomization (14.5% vs 16.2%, respectively; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.71 to 1.11). This sharply contrasts with the 28% RRR in the primary outcome noted in those receiving clopidogrel in association with percutaneous revascularization (95% CI, 0.57 to 0.90). Further analysis was able to demonstrate a strong trend toward benefit among those receiving clopidogrel in association with CABG during the initial hospitalization (RRR, 19%; 95% CI, 0.59 to 1.12); however, this effect was driven entirely by a reduction in the number of events prior to surgery (18% RRR in the primary outcome; 95% CI, 0.58 to 1.16), with no benefit noted in those receiving clopidogrel postoperatively (3% RRR; 95% CI, 0.74 to 1.26). Patients receiving postoperative clopidogrel also experienced a strong trend toward an excess of life-threatening bleeds (30% increased risk; 95% CI, 0.90 to 1.83).

Based on these findings, clopidogrel should not be routinely used in the postoperative management of patients undergoing CABG for treatment of NSTE-ACS. In fact, available data suggest that treatment with clopidogrel should probably be limited in the postoperative period to those who are intolerant of aspirin therapy. While speculative, it is possible that short-term cessation of clopidogrel treatment after surgery (median duration, 10 days) may have contributed to the failure of study investigators to demonstrate a benefit from postoperative clopidogrel. To further explore this, though, "a dedicated randomized clinical trial of clopidogrel plus aspirin vs aspirin alone after CABG" (5) is warranted.

Ty J. Gluckman, MD

Jeffrey J. Rade, MD

Steven P. Schulman, MD

The Johns Hopkins Hospital

Baltimore, MD

Reproduction of this article is prohibited without written permission from the American College of Chest Physicians (www.chestjournal. org/misc/reprints.shtml).

Correspondence to: Ty J. Gluckman, MD, The Johns Hopkins Hospital, Division of Cardiology, 600 N Wolfe St Carnegie 568, Baltimore, MD 21287; e-mail: tgluckml@jhmi.edu

REFERENCES

(1) Stein PD, Schunemann HJ, Dalen JE, et al. Antithrombotic therapy in patients with saphenous vein and internal mammary artery bypass grafts: the seventh ACCP conference on antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy. Chest 2004; 126(suppl):600S-608S

(2) Guyatt G, Schunemann HJ, Cook D, et al. Applying the grades of recommendation for antithrombotic and-thrombolytic therapy: the seventh ACCP conference on antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy. Chest 2004; 126(suppl): 179S-187S

(3) Yusuf S, Zhao F, Mehta SR, et al. Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med 2001; 345:494-502

(4) Fox KA, Mehta SR, Peters R, et al. Benefits and risks of the combination of clopidogrel and aspirin in patients undergoing surgical revascularization for non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome: the Clopidogrel in Unstable Angina to Prevent Recurrent Ischemic Events (CURE) trial. Circulation 2004; 110:1202-1208

(5) Bhatt DL, Chew DP, Hirsch AT, et al. Superiority of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients with prior cardiac surgery. Circulation 2001; 103:363-368

COPYRIGHT 2005 American College of Chest Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group