Psychotropic medications successfully combat symptoms of depression, anxiety and psychosis but fail spectacularly in reducing one crucial index of mental illness: suicide. A review of more than 71,000 patients in clinical trials of 52 psychotropic medications found an equal risk of suicide among those assigned medication and those taking placebos.

"Suicide may not be connected to alleviating symptoms [of mental illness]," says Arif Khan, M.D., medical director of the Northwest Clinical Research Center in Bellevue, Washington. "It is a complex behavior, much more complicated than the treatments for mental illness."

Khan reviewed Food and Drug Administration (FDA) reports on psychotropic drugs approved between 1985 and 2000 and calculated that the risk of suicide--11 per 100,000 in the general population--jumps to 752 per 100,000 in antipsychotic trials and 655 per 100,000 in trials of antidepressants. Khan also reviewed anti-panic, anti-anxiety and anti-obsessional agents. No class of medication showed a significant difference in the risk of suicide or attempted suicide among patients assigned to trial medication, FDA-approved medication or placebo.

Because clinical trials exclude patients thought to be at risk for suicide, or those suffering from comorbid mental illness, the rate of suicide calculated by Khan is surprisingly high. However, in general patients on placebos tend to drop out of trials earlier than those on medication, comparatively elevating the rate of suicide among patients taking psychotropic medication.

"Further research to identify psychotropics or other treatments that reduce suicide risk is essential" says Khan, who presented his findings at the New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit, an annual meeting sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health.

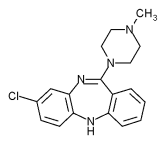

The atypical antipsychotic clozapine (marketed as Clozaril), is the sole medication currently under review by the FDA for use as an anti-suicidal agent.

COPYRIGHT 2002 Sussex Publishers, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2002 Gale Group