For several years the treatment of angina has been based on combinations of nitrates, beta blockers, and calcium antagonists. In the mid 1990s, there was concern about the long-term safety of calcium antagonists. Poole-Wilson and colleagues studied the effect of the long-acting calcium agonist nifedipine (Procardia) on patients with stable angina pectoris in the ACTION study (A Coronary disease Trial Investigating Outcomes with Nifedipine Gastrointestinal Therapeutic System).

More than 7,600 patients with stable angina pectoris from 291 treatment facilities in 19 countries were recruited for the study. Patients were 35 years or older and required oral or transdermal therapy to prevent or control symptoms. Reasons for exclusion included left ventricular ejection fraction less than 40 percent, overt cardiac failure, major cardiovascular event or intervention in the previous three months, significant cardiac valvular or pulmonary disease, and unstable insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus.

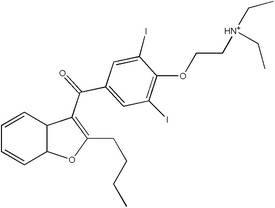

Nifedipine or placebo was added to current therapy depending on randomization. The initial dose of nifedipine was 30 mg daily. If tolerated, this was increased to 60 mg daily within six weeks. Other medications were continued at the discretion of the treating physician except for calcium antagonists, cardiac glycosides (except for supraventricular arrhythmia), positive inotropic agents, antiarrhythmic agents in classes I or III other than amiodarone (Cordarone) or sotalol (Betapace), cimetidine (Tagamet), antipsychotic agents, antiepileptic drugs, and rifampin (Rifadin). Randomization was made following baseline assessment that included a full medical history, echocardiography, blood pressure assessment, and classification into a New York Heart Association (NYHA) category. At each six-month follow-up, clinical assessment included NYHA status, vital signs, and monitoring for adverse effects. The study assessed survival without a major cardiovascular event. This was measured as time to occurrence of acute myocardial infarction, refractory angina, new overt heart failure, debilitating stroke, peripheral revascularization procedure, or death from any cause. The primary combined endpoint was death from any cause, acute myocardial infarction, and debilitating stroke. Other cardiovascular events were predefined as secondary outcomes.

The 3,825 patients randomized to nifedipine were comparable with the 3,840 randomized to placebo. The average age was 63.5 years, and 79 percent of participants were men. One half of the participants had experienced myocardial infarction, and one fourth had undergone a coronary revascularization procedure. Nearly 70 percent had significant lesions on coronary angiography, and 46 percent had NYHA classification of II or III. By six weeks, 88 percent of patients were taking the full dose of medication. Sixteen percent of patients reduced nifedipine to half-dose. Therapy was discontinued by 34 percent of patients taking nifedipine and 31 percent of those receiving placebo. The most common adverse events leading to discontinuation of nifedipine were peripheral edema and headache.

The mean follow-up achieved was almost five years. Patients taking nifedipine experienced significant increases in heart rate and reductions of blood pressure compared with the placebo group. Cardiovascular and noncardiovascular death rates were similar in the two groups. Patients treated with nifedipine had significant reductions in new overt heart failure, coronary angiography, and bypass surgery. Overall, nifedipine prolonged mean event-free survival by 41 days, mainly because of a reduction in coronary angiography.

The authors conclude that nifedipine is safe in patients with stable angina pectoris already using conventional treatments and is associated with a reduction in coronary procedures and interventions. The death rate in patients assigned to nifedipine was 1.1 per 1,000 patient-years greater than the placebo group, but most of these deaths were not because of cardiovascular causes. No evidence was found indicating that nifedipine induces myocardial infarction or heart failure.

ANNE D. WALLING, M.D.

Poole-Wilson PA, et al. Effect of long-acting nifedipine on mortality and cardiovascular morbidity in patients with stable angina requiring treatment (ACTION trial): randomized controlled trial. Lancet 2004;364:849-57.

COPYRIGHT 2005 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group