One of the miracles recounted in the New Testament was that of the long-paralyzed man who was commended to stand up and walk.

On the morning of Sept. 21, 1948, an almost as miraculous event began to unfold. A 29-year-old woman, hospitalized at the Mayo Clinic for rheumatoid arthritis so severe that the painful joints of her legs had been locked into immobility, was injected with a tiny amount of an experimental new drug. Unlike the Biblical event, nothing happened immediately.

But here too, faith intervened, faith on the part of a physician, Philip Showalter Hench, who had devoted much of his career to finding a way to cure or alleviate arthritis. So, despite the apparent failure of the injection, Hench persisted, giving a second injection the next day, still without apparent effect.

But when the patient awoke on the third day, she found to her amazement and joy that the pain had disappointed and that she could swing her legs over the side of the bed and actually walk. Within a week she left in the hospital to go on a three-hour shopping spree. Thirteen other severely afflicted patients were also given injections of the new drug, then called compound E. The results were uniformly incredible. Crutches and wheels chairs discarded. Frozen joins turned supple. Swelling and pain largely eliminated.

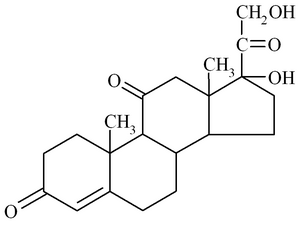

The new drug was the fruit of a long, patient, often discouraging effort by an American physician, Edward Kendall. Produced by the body in a section of the adrenal gland called the cortex, the drug was found to belong to a widely diverse family of chemicals, called steroids, that includes vitamin D, male and female sex hormones, and the heart drug digitalis.

All of the steroid hormones produced by the adrenal gland, now known as the corticosteroids, influence directly or indirectly many of body's basic chemical processes. Their main function is to help the body maintain the chemical status quo against disruptive forces. Those factors, all forms of stress, include illness, injury, infection, mental strain, severe exertion, and allergic reaction. Without the adrenal cortex and its products, the body would succomb to the impact of such stress.

One of the corticosteroids found by Kendall, which he called compound B, is now known as corticosterone; another, compound F, we know as cortisol or hydrocortisone; and compound E, which gained instant fame that September day, has become accepted as a general term for the whole class of these powerful drugs--cortisone.

Hench's success in applying cortisone to arthritis happened at a time when first the sulfa drugs and then penicillin and other early antibiotics were revolutionizing medicine and introducing the terms "wonder drug" and "miracle medicine" to our common vocabulary. Great things were expected of cortisone, and it was delivering. As one physician put it, "Not only were patients previously crippled with arthritis helped to get back on their feet and become active members of society again, but patients with other so-called 'collagen diseases' such as disseminated lupus erythematosus and and polyarteritis nodosa were dramatically benefited; patients with allergies such as bronchial asthma, hay fever, and eczema received impressive relief; patients with some types of leukemia and other malignancies went into temporary remissions; and those with numerous other disorders experienced unprecedented improvement from those agents." In addition, a once fatal affliction. Addison's disease, resulting from a defective adrenal cortex, could now be treated successfully.

It is not surprising, then, that cortisone came to be accepted as a miracle medicine or that within two years Hench and Kendall, together with Swiss researcher Tadeus Reichstein, were sharing the Nobel Prize for medicine and physiology.

But before this miracle could come within reach of those who so desperately needed it, the price had to be brought down. Due to the difficulty of synthesizing cortisone from ox bile, it was over a thousand times more costly than gold. An intense research effort to reduce the cost was immediately undertaken. This required some incredibly complicated chemical footwork, since an oxygena atom had to be dislodged from its normal place on the steroid framework and moved to another point. This was accomplished, and soon the basic cortisone building block was being produced from steroids in soybeans. Mexican yams, cholesterol in wool fat, and yeast. Within a year, the cost had been reduced by 95 percent. Research to synthesize analogues, or chemical variations, of cortisone was also soon under way.

But even while all this intense research was proceeding, and amidst all the acclaim, awards and great expectations, the miracle was already turning sour. Many patients, quickly reverted to their previous condition when the cortisone treatment ceased. And--even worse--devastating and frigtening side effects often accompanied cortisone treatment. In many instances, those treated exhibited all the symptoms of adrenal excess, called Cushing's disease. Side effects included insomnia, psychotic behavior, growth suppression in children, peptic ulcer, delayed wound healing, hyperglycemia (excessive sugar in the blood), carbohydrate intolerance, muscle weakness, susceptibility to infections, and many others. Surgeons reported death under general anesthesia of patients undergoing minor surgery who had been taking cortisone. In addition, cortisone proved to have a habit-forming potential--stopping the drug often brought on withdrawal symptoms such as fatigue, weakness, arthralgia (joint pain), fever dizziness, lethargy, depression, fainting, dyspnea (difficult breathing), anorexia, and even death.

Where physician and patient alike had been attracted to the miracle of cortisone, they were now repelled. As one expert, Dr. William McK. Jeffries, put it, many physicians who once extolled its virtues now "denounced it as dangerous drug whose use is not justified except in critical illnesses or emergencies." Yet others defended cortisone as a useful therapeutic tool whose hazards had been exaggerated and whose dangers stemmed from excessive dosages, not from the drug itself. They pointed out that injection of cortisone preparations into the joints to relieve the pain and immobility of arthritis is relatively safe and effective if only a few joints are involved. And, of course, for patients suffering from adrenal insufficiency, no one would argue that this therapy is not required.

Where then is the truth about cortisone? Much of the disillusion may have stemmed from an incomplete understanding of what the drug actually does. Generally speaking, cortisone (used as a blanket term for all the corticosteroids) does not cure--it suppresses symptoms. Inflammation--localized heat, redness, swelling and pain--is a symptom. And arthritis is a form of inflammation. Kept withing proper limits, inflammation is part of the body's defense mechanism and a means of dealing with injury or infection. Where inflammation has burst through these limits, as in arthritis, treatment with cortisone can be beneficial. But if cortisone treatment suppresses the inflammation reaction to injury or infection or reduces it to an ineffective level, thee result can be very harmful: It disguises the fact that the underlying infection is still at work and it eliminates one of the ways by which the infection is controlled.

Further, too much cortisone can produce all the symptons of an overactive adrenal cortex (Cusghing's disease). Paradoxically, too much cortisone can sometimes produce just the opposite effect--the symptoms of adrenal insufficiency, or Addison's disease. This latter outcome stems from the fact that when a patient is being treated with any of the corticosteroids the body's master gland, the pituitary, responds to what it detects as an excess amount of these compounds. Like a chemical thermostat, the pituitary in turn instructs the adrenal cortex to ease off from its corticosteroid production chore. Then, if treatment with corticosteroids is suddenly stopped, there is an insufficient flow from the resring cortex, and the patient shows all the signs of Addison's disease--weakness, weight loss, and pigmentation of the skin and mucous membranes.

There are still other internal reactions to cortisone (corticosteroid) treatment, some quite serious. It is clear that these are very potent drugs, to be treated with respect and used with care and delicacy.

Today, synthetic analogues of cortisone have largely replaced the original form of the drug. While cortisone itself is rarely prescribed, there are no less than 30 cortisone-like drugs of varying potencies loosely, though incorrectly, called "cortisone." These are divided into two families, the glucocorticoids and the mineralocorticoids. These synthetic analogues vary widely in potency, in chemical formulation, and in mode of delivery, although all are principally used to treat various forms of inflammation.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved these various forms of cortisone as safe and effective--when used appropriately--for treating Addison's disease; for symptomatic relief of inflammation due to a variety of causes, such as rheumatic fever and tuberculosis; for immunosuppression (helping control the rejection reaction accompanying rogan transplants) for cancer therapy (especially lymphoctic leukemia, Hodgkin's disease, and breast cancer); and for a variety of other ailments, such as bronchial asthma and hypercalcemia (excessive calcium in the blood).

FDA approval includes detailed guidance to physicians in the drug labeling that covers such matters as the illnesses for which the drug is approved, existing conditions that preclude its use (contraindications), lists of common side effects and adverse reactons, warnings, and other precautions. Using cortisone--as with any drug--requires the physician to carefully weigh risks against benefits. Less hazardous drugs for the condition being treated should be considered first. The lowest effective dose should be prescribed. All dosages should be individualized, based on the patient's condition, age, illness and other factors.

An important development in reducing the adverse side effects of cortisone-type drugs is alternate-day therapy. The adverse consequences of the drug are mitigated by giving the body a day's rest between doses. This innovation was pioneered by Dr. John G. Harter, now with FDA.

The labeling approved for prednisone, a glucocorticoid, can serve as an example of the kind of information FDA requires physicians to have for any cortisone-type drug. The descriptive information tells prednisone's intended therapeutic effects--fundamentally, symptomatic relief from inflammation in any tissue. It states that the drug is effective in most tissues throughout the body regardless of the cause of the inflammation. It also notes that the way prednisone works is not completely understood but it is thought to inhibit several mechanisms within the tissues that induce inflammation. The labeling points out that prolonged or excessive use of prednisone can impair body's disease-fighting mechanisms.

The labeling also warns physicians that prednisone should not be taken by anyone with a systemic fungal infection. It advises special caution in prescribing the drug for patients who have hyperthyroidism, cirrhosis, ulcerative colitis, renal unsufficiency, high blood pressure, osteoporosis, tuberculosis, and a number of other conditions.

The information available to the physician also discusses the amount of time required for apparent benefit (usually 24 to 48 hours); the natural, expected and unavoidable side effects (salt and water retention, weight gain, increased sweating, appetite, and susceptibility to infection, among many others); and the unusual, unexpected and infrequent reactions, both mild and serious. In addition, the labeling cautions against discontinuing the drug abruptly, advises that the patient carry a card to alert medical personnel that the drug is being taken, and gives special guidance about vaccinations while taking prednisone.

The comprehensive nature of these labeling instructions (essentially the same for all the cortisone-type drugs) is commensurate with their powerful nature and is necessary to help ensure that they are used safely and effectively.

As an indication that cortisone can be quite safe when used properly, FDA in 1979 permitted nonprescription dispensing of hydrocortisone and hydrocortisone acetate at one-half percent strength in topical preparations--those designed to work only on the areas of the skin to which they are applied. The drugs are available as lotions, aerosols, creams and ointments for a variety of minor skin disorders. These include irritations, itches and rashes due to dermatitis, eczema, insect bites, mild poison ivy, oak and sumac, reactions to detergents and jewelry, and minor itching of the genital and rectal areas.

An essential condition for over-the-counter dispensing of hydrocortisone and hydrocortisone acetate is cautionary labeling for consumers detaling the conditions for which the product could be used, when it should not be used, its length of use, and so forth. For example, since some skin conditions may result from a serious underlying disease, the labeling must state that the product should be discontinued and a physician consulted if the symptoms persists for more than seven days or clear up and then recur within a few days.

Although prolonged topical application of some prescription corticosteroids have been associated with development of such skin conditions as stretch marks, acne, blood vessels becoming visible, bruises and paper-thin skin, and although there have been reports suggesting growth retardation after chronic use by children, such reactions are rarely associated with nonprescription topical hydrocortisone.

Ralph Waldo Emerson once said, "Nature never gives anything to anyone; everything is sold. It is only in the abstractions...that choice comes without consequences." In choosing to discover, develop and deploy cortisone, scientists and physicians have also learned the cost and the consequences. But there are very real benefits, and it is the task of both the art and science of medicine and pharmacy to minimize the cost while attaining all the benefits.

COPYRIGHT 1985 U.S. Government Printing Office

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group